Conduction cooking principles involve the heating of something that is cool by placing it in contact with something that is hot. In cooking, an example of this is when one places a pot or a pan on a stove. As the stove heats the pot or pan the heat is transferred to whatever is in the pot or pan, thus cooking it.

For example, when one places a pot of water on the stove the heat transfer causes the water to boil. Drop an egg into the boiling water and the heat is transferred first to the egg whites and then to the yolk, eventually creating a soft or hard-boiled egg depending on how long one cooks the egg.

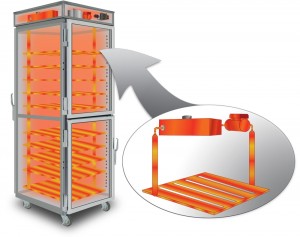

Check out our conduction cooking video here to learn more about how Theromdyne’s patented FluidShelf Technology works!

When frying something, the same principle applies. The heat of the stove is transferred to the pan, then to the oil, and finally to the food being fried, such as breaded chicken, cooking it from the outside in as the heat is transferred from the skin and breading down to the meat.

How efficiently heat is conducted depends on the conductivity of what is being heated. Copper is a pretty good conductor of heat whereas stainless steel is not. Water is a poor conductor of heat. Indeed food is also a poor conductor, which is one reason that – for example – a roast will continue to cook for several minutes after it is taken off the heat source. That is one reason a lot of recipes suggest letting a food item “rest” after the official cooking time is done to allow it to finish cooking and cool just a little to allow for handling, such as chopping and slicing.